Special for the Armenian Weekly

In 2015, the on-again, off-again fighting between Armenian and Azerbaijani forces continued a trend towards escalation that was

already significant in 2014. In the last 12 months, the Armenian forces have seen a more-than-50-percent increase in conflict-related casualties; judging by information leaks in spite of Azerbaijani military censorship rules, a similar increase is likely on the other side as well.* This means that the total conflict-related death toll exceeded 100 people last year.

Armenian soldiers patrol near the border with Azerbaijan in 2012. (Photo: AFP/Karen Minasyan)

The immediate point of this fighting is not to win any territory, but to kill as many adversary personnel as possible, increasing the cost for the status quo without escalating to a more risky full-scale war. One case of such warfare is the Arab-Israeli fighting between 1967 and 1970—known as

the War of Attrition; by various estimates both sides of that fighting lost as many or more people in 3 years of “low-intensity” warfare than during the 6 days of full-scale war in 1967—several thousand for both sides.

Compared to the 1967-70 war, the Armenian-Azerbaijani fighting remains at the lower end of intensity. In 2015, on the Armenian side, the fatalities included 42 military personnel and 5 civilians, compared to 27 military and 6 civilians in 2014. Twenty-four of the military personnel were enlisted young men in their late teens and early 20s, 9 were older contracted servicemen, and 9 were officers. According to information available, 20 of the deaths resulted from direct combat engagements (raids and ambushes), 16 from sniper fire and other light arms shelling, and 6 from heavier artillery and mortar shelling.

Most of the fighting was concentrated in Nagorno-Karabagh’s northern Mardakert district, where at least 16 Armenian servicemen were killed in combat. Half of these 16 fatalities occurred in 2 incidents: 4 servicemen were killed and more were wounded in the March 19 ambush in a forested area between Gulistan and the Yeghishe Arakyal Monastery, and 4 more were killed and over a dozen injured when on Sept. 25 Azerbaijani artillery struck an army training center in the open area just off the Madagiz-Talish Road, 3 kilometers from the Line of Contact (see

map for these locations).

All of the five civilian fatalities and six military personnel were killed in Armenia’s northeastern Tavush province, near the towns of Noyemberian and Berd. On September 24 Tavush villages located in the immediate proximity of the border came under intense mortar fire that killed three women and wounded four other civilians.

Heavier Weapons and Better Reconnaissance

Starting in late 2014, Azerbaijan began to regularly fire mortars—a kind of intermediate step between light arms and the sniper warfare of the past and higher-caliber artillery shelling. Towards the end of 2015, Azerbaijan also used D-30 howitzers (in at least two incidents, including in the Sept. 25 attack) and tanks.

Armenian military scouts attend a performance to mark the annual celebration»of the Armenian Armed Forces, 2013 (Photo: AFP/Karen Minasyan)

The Armenian military estimated that throughout the year Azerbaijani forces fired a total of 20 125mm tank shells; 34 122mm D-30 shells; 416 120mm mortar mines; 574 TR-107 107mm rockets; and more than 10,000 82mm and 60mm mortar mines. The Armenian counter-attacks were limited to mortar fire, mostly 60 and 82mm, but judging by drone-shot footage released by the Armenian military those retaliatory strikes were both devastating and deadly.

The use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) is altering warfare around the world, and that has been the case in Karabagh as well. Azerbaijan began to acquire UAVs from Israel in 2008 and Armenia began domestic production soon after, but their use in Karabagh really intensified over the past two years. This means that both sides now have more accurate and timely intelligence about the location of the other side’s forces. If in the past most of the attacks were conducted on frontline sentry positions and trenches, where soldiers are better protected from shelling and are harder to kill, over the past year there has been a notable shift to attacks against moving targets that are more exposed.

Political Significance

The immediate aim of the Azerbaijani-initiated attrition warfare is mounting psychological and political pressure on the Armenian leadership by increasing Armenian casualties. It was no coincidence that fighting escalated just before meetings between the Armenian and Azerbaijani foreign ministers in New York in September and the presidents in Bern, Switzerland, in December. There were also stretches of quiet time, starting around the time of the Armenian Genocide Centennial on April 24 and continuing through the European Games hosted by Baku in June. Statements by the Russian Foreign Ministry urging restraint—made at the height of fighting in late September and mid-December—also had a calming effect.

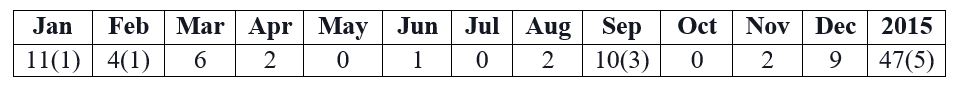

This ebb and flow in fighting is reflected in how Armenian conflict-related fatalities were reported month to month; in the table below, total fatalities (including civilians) are shown:

While comprehensive data for Azerbaijani fatalities is no longer available, fragmentary information that

is available follows a similar pattern.

Judging by official Azerbaijani communications, they have two main constituencies: First is the Azerbaijani public, which is assured of the country’s military dominance through exaggeration of Armenian casualties and the prohibition of unofficial reports about Azerbaijani losses. With plummeting energy revenues and major currency devaluation, nationalist rallying on Karabagh is an important crutch for the government. Second is the Armenian public. Azerbaijani leadership must be hoping that over time, through a combination of greater population numbers and greater domestic repression, they will be in a better position to cope with the costs of attrition fighting than the Armenian side.

Much of the commentary about the Karabagh conflict continues to focus on two extreme scenarios of its development: full-scale, all-out war; or all-out peace through political resolution. The experience of the last two years points in the direction of something in-between: continued and escalating attrition war.

*The Armenian military news site

Razm.info (in Armenian and Russian) has detailed these leaks—as well as the Azerbaijani government’s efforts to suppress them—throughout the year.

Special for the Armenian Weekly In 2015, the on-again, off-again fighting between Armenian and Azerbaijani forces continued a trend towards escalation that was already significant in 2014. In the last 12 months, the Armenian forces have seen a more-than-50-percent increase in conflict-related casualties; judging by information leaks in spite of Azerbaijani military censorship rules, a similar increase is likely on the other side as well.* This means that the total conflict-related death toll exceeded 100 people last year. Armenian soldiers patrol near the border with Azerbaijan in 2012. (Photo: AFP/Karen Minasyan) The immediate point of this fighting is not to win any territory, but to kill as many adversary personnel as possible, increasing the cost for the status quo without escalating to a more risky full-scale war. One case of such warfare is the Arab-Israeli fighting between 1967 and 1970—known as the War of Attrition; by various estimates both sides of that fighting lost as many or more people in 3 years of “low-intensity” warfare than during the 6 days of full-scale war in 1967—several thousand for both sides. Compared to the 1967-70 war, the Armenian-Azerbaijani fighting remains at the lower end of intensity. In 2015, on the Armenian side, [...]

Special for the Armenian Weekly In 2015, the on-again, off-again fighting between Armenian and Azerbaijani forces continued a trend towards escalation that was already significant in 2014. In the last 12 months, the Armenian forces have seen a more-than-50-percent increase in conflict-related casualties; judging by information leaks in spite of Azerbaijani military censorship rules, a similar increase is likely on the other side as well.* This means that the total conflict-related death toll exceeded 100 people last year. Armenian soldiers patrol near the border with Azerbaijan in 2012. (Photo: AFP/Karen Minasyan) The immediate point of this fighting is not to win any territory, but to kill as many adversary personnel as possible, increasing the cost for the status quo without escalating to a more risky full-scale war. One case of such warfare is the Arab-Israeli fighting between 1967 and 1970—known as the War of Attrition; by various estimates both sides of that fighting lost as many or more people in 3 years of “low-intensity” warfare than during the 6 days of full-scale war in 1967—several thousand for both sides. Compared to the 1967-70 war, the Armenian-Azerbaijani fighting remains at the lower end of intensity. In 2015, on the Armenian side, [...]

[img][/img]

More...