|

|

|

|

|

VIP Forums Muzblog Chat Games Gallery. Ôîðóì, ìóçäíåâíèêè, ÷àò, èãðû, ãàëëåðåÿ. |

||||

|

||||||||

| Diaspora News and events in Armenian and other diasporas. |

An Unstated Promise: Armen Marsoobian’s ‘Memory Project’ |

LinkBack | Thread Tools | Display Modes |

|

|

#1 (permalink) |

|

Top VIP VIP Ultra Club

Join Date: Jan 1970

Posts: 12,055

Rep Power: 69

|

Special for the Armenian Weekly

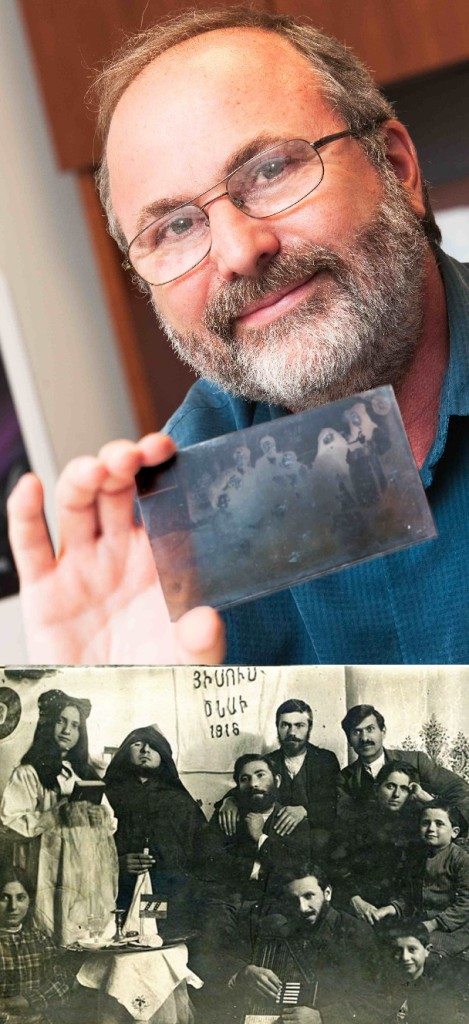

Marsoobian holding an original glass negative of the photo below—one of 600 in his possession (Photos: southernct.edu/Armen T. Marsoobian) Marsoobian holding an original glass negative of the photo below—one of 600 in his possession (Photos: southernct.edu/Armen T. Marsoobian)When this gathered material was given to Marsoobian after one of his uncles passed away, he decided to take it upon himself to tell the world his family story. “Even though my uncle never explicitly told me that I had to carry this project out, I really felt that I was completing something they started. I felt it was important to give that whole generation a voice. In a way, I felt I was fulfilling a moral obligation—an unstated promise. That, in a way, was my chief motivation,” he says. Nearly three years ago, Marsoobian, a professor of philosophy at Southern Connecticut State University and chair of the philosophy department, decided that perhaps it would be best to tell the story of his family through photographic exhibitions. He also felt that his family’s story could be a way to present to the people of Turkey the greater story of the Armenian presence in those lands before and during the Armenian Genocide. And so, in April 2013, Marsoobian launched his exhibitions at Istanbul’s DEPO, a center known for hosting collaborative projects and various cultural and artistic exchanges, located in an ancient four-storey former tobacco warehouse in Istanbul’s Tophane neighborhood. Since then, he has held exhibitions in other parts of Turkey, including in Ankara and Diyarbak?r. But perhaps it was his October 2013 exhibition in the town of Merzifon (Marsovan) in Turkey’s central Black Sea region that meant the most. “It was particularly gratifying to bring it to that location [Merzifon] because it was a homecoming in a way,” Marsoobian explains. His family was forced to leave the town in 1921—and would ultimately leave Turkey in 1922. “Besides the understandably horrible memories from that period, there were many beautiful memories. So in a way, the exhibition was a way to bring those photographs back home,” he explains, describing the decision to hold an exhibition there as both morally and emotionally satisfying for him. “The exhibitions—at least the ones I’ve had in Turkey—have had a lot of textual material to go along with the photographs,” Marsoobian says. These texts present a family narrative that provides context about what was really going on in the region at the time. “It really traces the family trajectory from the 1870’s until they leave Turkey and arrive in Greece in 1923,” he explains. Marsoobian’s exhibitions aren’t mere images with captions; there is actually much reading to do at his displays. “I have been fortunate to work with people in Turkey who have translated my words into Turkish. There is a real educational component to it—it’s not just looking at pictures,” he says. Though the exhibitions are deeply personal, Marsoobian also recognizes the political aspect of displaying these photographs in Turkey. For him, the exhibitions have a clear political objective of what he calls “opening up conversation and dialogue” about the Armenian presence in Turkey—a missing component of Turkey’s history, according to Marsoobian. “Many people in that society are completely ignorant of it because of the way the national educational policy has erased the Armenian presence. I found it very satisfying when people were so amazed by seeing the photographs of their own cities, their own towns, and how little they knew about the cultural and educational level of this [Armenian] community that no longer exists.” According to Marsoobian, the exhibitions were well received—at least, in his personal interactions. “There have been some negative things written and published. Most recently, the Ankara exhibition [November 2015] caused perhaps the most negative reaction,” he explains. The negative reaction Marsoobian describes was in part directed against the ?ankaya municipality since, for the first time, the exhibition was held in a municipal arts center. ?ankaya is considered the “downtown municipality” of Ankara; it is where much of the country’s power—the parliament, the prime minister’s residence, and many government buildings—is centered. “The mayor of ?ankaya is a member of the CHP [Republican People’s Party], so he got a lot of criticism in the AKP [ruling Justice and Development Party] press, as well as the more nationalist press. Also, there was criticism against the mayor’s office in social media because of it,” Marsoobian says. In the wake of the bad press and denigration, the mayor’s office put out a statement distancing itself from the exhibition, stating that it did not necessarily endorse its content. Not all of the press in Turkey has been so critical, though. “Taraf [a national newspaper in Turkey] actually ran a front-page article about it [the exhibitions] and in the opening paragraph, they used the Turkish word for the Armenian Genocide—Ermeni soyk?r?m—without the use of scare quotes, which, for 2013, I thought was quite ground-breaking,” he said.  Marsoobian’s ancestors Tsolag Dildilian, Aram Dildilian, and Haiganouch Der Haroutiounian (n?e Dildilian) worked diligently to save their families and the few who had managed to escape the deportations (Photo courtesy of Armen T. Marsoobian) Marsoobian’s ancestors Tsolag Dildilian, Aram Dildilian, and Haiganouch Der Haroutiounian (n?e Dildilian) worked diligently to save their families and the few who had managed to escape the deportations (Photo courtesy of Armen T. Marsoobian)Ankara is not home to many Armenians, but some of those who remained in the area came to see his exhibition. “They were just ecstatic about the fact that this can be done and that it’s open—in many ways they [Armenians] have had to live their lives under the radar in many parts of Turkey,” he explains. Marsoobian’s exhibitions have not been limited to Turkey. He has presented several versions of his exhibitions across the United States, London, and Yerevan. “The topic is the same, but the design of the exhibitions can vary depending on where it’s being held.” Although a date has not yet been set, Marsoobian hopes to hold an exhibition in Watertown, Mass., in the coming months. “We were originally scheduled for November 2015 at ALMA [Armenian Library and Museum of America]; however, it became logistically impossible with all the other exhibitions I was holding. I’m hoping that we can soon set a date for autumn 2016,” he says. In his new book, Fragments of a Lost Homeland: Remembering Armenia, published in May 2015, Marsoobian brings to life the extensive collection of family materials that depict his ancestors’ survival against overwhelming odds during the Armenian Genocide. He uses memoirs, diaries, letters, photographs, and drawings to tell their story. “It is perhaps most important for me that this work is made available to the Turkish people,” he says. The translation of the book into Turkish was completed last summer and he hopes that the Turkish version of the book will be published by spring. “It’s all a part of what I call my ‘memory project’. Our story must reach the people of Turkey.” In this quest, Marsoobian’s bilingual Turkish-English photography book, Dildilian Brothers: Photography and the Story of An Armenian Family in Anatolia, 1888-1923, was published in Turkey by Birzamanlar Publishing House just last month. The publication of his books do not seem to be the conclusion to Marsoobian’s self-described “ongoing project.” He has plans for an exhibition in Izmir next. When asked why he chose that particular city, Marsoobian explains that the city is more cosmopolitan than other parts of Turkey, and thus more open to such a presentation. “There is a good venue there that is under the more progressive municipality. The exhibitions don’t have anything to do with Izmir, since the family had no direct connection to the city. But Izmir—as many of us know—had a significant Armenian community, which was destroyed in the War of Independence,” says Marsoobian. “My mission is to bring it to all cities that had a significant Armenian population before the genocide.” Two cities with a family connection are Sivas (Sebastia) and Samsun, although that may prove to be problematic due to what he calls heightened nationalism in those areas. “Though I’ve been to both places, and have made contacts with people there, it will be difficult. But we will see. This is a long-term project. Like I said, I call it my ‘memory project,’ and it will continue.” “In a way, I am trying to do my small part in influencing the collective memory of Turkish citizens. We have to be careful. Getting the story there is more important than just being able to push the Armenian cause. I want to get them to start thinking about it, how they were denied this history. I want them to fill in the blanks.” Special for the Armenian Weekly Marsoobian holding an original glass negative of the photo below—one of 600 in his possession (Photos: southernct.edu/Armen T. Marsoobian) Armen T. Marsoobian’s two uncles began gathering family photographs, memoirs, and letters in the 1980’s—anything that they thought would help retrace their family story. “They tried to put it together themselves, to tell the family story—a fascinating one that captures so much of our people’s history,” Marsoobian explains. In the early years of the 20th century, his family members bore witness to the Armenian Genocide. And through their memoirs, it was clear they struggled to ensure “that people understood what happened to the Armenians.” When this gathered material was given to Marsoobian after one of his uncles passed away, he decided to take it upon himself to tell the world his family story. “Even though my uncle never explicitly told me that I had to carry this project out, I really felt that I was completing something they started. I felt it was important to give that whole generation a voice. In a way, I felt I was fulfilling a moral obligation—an unstated promise. That, in a way, was my chief motivation,” he says. Nearly three [...] Special for the Armenian Weekly Marsoobian holding an original glass negative of the photo below—one of 600 in his possession (Photos: southernct.edu/Armen T. Marsoobian) Armen T. Marsoobian’s two uncles began gathering family photographs, memoirs, and letters in the 1980’s—anything that they thought would help retrace their family story. “They tried to put it together themselves, to tell the family story—a fascinating one that captures so much of our people’s history,” Marsoobian explains. In the early years of the 20th century, his family members bore witness to the Armenian Genocide. And through their memoirs, it was clear they struggled to ensure “that people understood what happened to the Armenians.” When this gathered material was given to Marsoobian after one of his uncles passed away, he decided to take it upon himself to tell the world his family story. “Even though my uncle never explicitly told me that I had to carry this project out, I really felt that I was completing something they started. I felt it was important to give that whole generation a voice. In a way, I felt I was fulfilling a moral obligation—an unstated promise. That, in a way, was my chief motivation,” he says. Nearly three [...] [img][/img] More... |

|

|

|

|

|

|