|

|

|

|

|

VIP Forums Muzblog Chat Games Gallery. Ôîðóì, ìóçäíåâíèêè, ÷àò, èãðû, ãàëëåðåÿ. |

||||

|

||||||||

| Diaspora News and events in Armenian and other diasporas. |

|

Yessayan’s Literary Testimony Details Adana Massacres |

LinkBack | Thread Tools | Display Modes |

|

|

#1 (permalink) |

|

Top VIP VIP Ultra Club

Join Date: Jan 1970

Posts: 12,055

Rep Power: 69

|

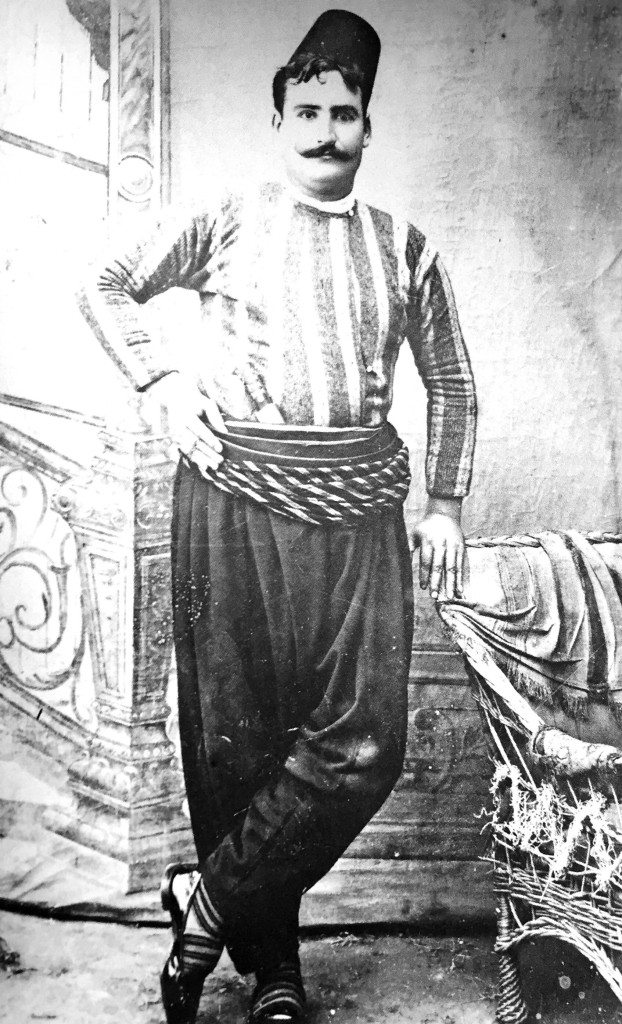

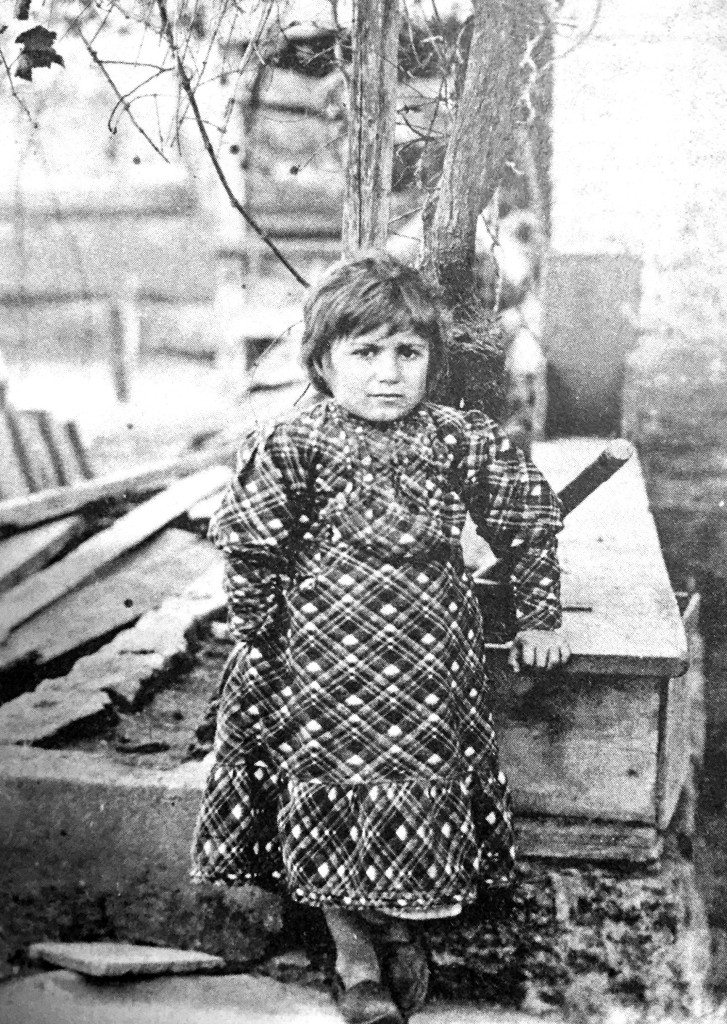

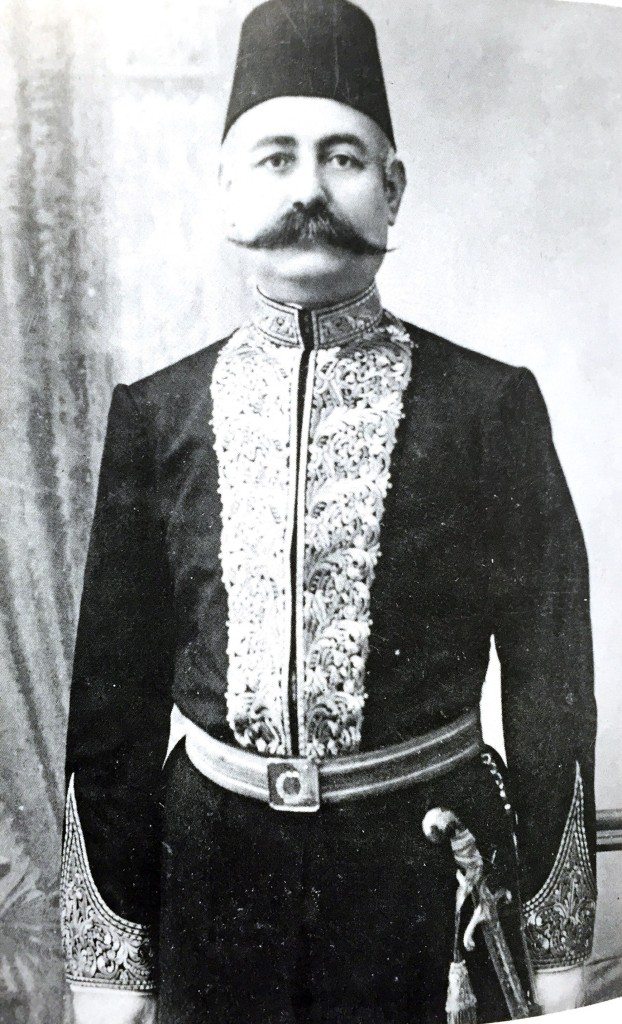

Special for the Armenian Weekly

In the year of the Armenian Genocide Centennial, we saw hosts of books published on the genocide, attended many inspiring presentations, and began what we hope will be productive conversations to chart a course toward reparations. The Adana Massacres that began in April 1909, however, are sometimes overlooked, sandwiched as they were between the Hamidian Massacres of 1895-96 and the 1915 Armenian Genocide. These attacks in 1909 took the lives of more than 30,000 Armenian men, women, and children. Armenian Cilicia had been burned to the ground, many of its people trapped inside torched churches, leaving only charred bones to speak of their fate. Thousands of children were left orphaned or with broken, widowed mothers who could no longer care for them. The number of unprotected women, those who had lost husbands, fathers, and brothers, was over 10,000. Only two towns were left standing by September of 1909—Sis and Dortyol. The revolution of 1908 had reestablished the Ottoman Constitution, resulting for a short time in the lifting of censorship, the release of political prisoners, and a sense of hope that enhanced freedoms would be forthcoming. Many Armenians believed that the restoration of this constitution would change their status for the better and celebrated it publicly, singing songs of freedom and hope. A few were not convinced, among them members of my family who decided that the situation was so volatile that they would move to an Armenian town—Dortyol—where they would at least have the help of their own people in the event of catastrophe, which indeed soon followed. The constitution was “false,” as my great uncle Mihran Der Melkonian said to his family, and death and chaos soon came to Armenian Cilicia.  Zabel Yessayan, seated in center, with other m embers of the delegation sent to Adana from Constantinople by the Armenian Patriarchate (Photo: AGBU Nubarian Library, Paris, France) Zabel Yessayan, seated in center, with other m embers of the delegation sent to Adana from Constantinople by the Armenian Patriarchate (Photo: AGBU Nubarian Library, Paris, France)Perhaps her most significant work was a masterpiece of literary testimony. In 1909, she was appointed by the Patriarchate of Constantinople to a delegation sent to Adana to aid orphans and assess and report on conditions in Cilicia after the massacres. She recorded her experiences in her book In the Ruins, which was translated into Turkish and French, and now English. The Armenian International Women’s Association (AIWA) has fortunately made this crucial work available, translated by the expert G.M. Goshgarian. This brief biography of Yessayan and the foreword written by Judith Saryan, Danila Jebejian Terpanjian, and Joy Renjilian-Burgy in this edition provide important information about the author and the book’s context. The editors point out that the Hamidian Massacres of the mid-1890’s and the Adana Massacres are considered “precursors” to the 1915 Armenian Genocide. While it is certainly true that historians can find key differences between these three instances of mass murder, the threads of racism, hatred, and greed that can lead to massacres underlie all three of these historical moments, however much we can parse their specific origins. Yessayan’s book is both a masterwork of literary testimony and an original source of crucial details about the Adana Massacres and their aftermath. The editors rightly focus on the genre definition of Yessayan’s book, offering Marc Nichanian’s statement that “In the Ruins is…a book of testimony, and without a doubt the only book in Armenian where bearing witness becomes literary.” Although I suggest that some survivor narratives could achieve the designation “literary” as well, a first-person narrative of one’s own experience of genocide is of a different order than what Yessayan is doing—willingly bearing witness to the horrors of others, and doing so with grace and power. This is what makes it a work of literary testimony. She has chosen to become the survivor of secondary trauma, to bear witness, and indeed, this is evident throughout the book as she struggles to capture the horror of what she has seen without succumbing to it. But Yessayan has another job as well: She is Dante’s traveler who must remain whole in order to be of help. She is attempting to chronicle both her efforts to aid the victims of these atrocities and their experience of those atrocities. To do this she must be outside the experience and inside it at the same time. A poignant example of her empathy and desire to impart this to her readers is the epigraph that begins chapter 4, “The Orphans”:  Missak Sarkisian, one of the Armenians who was publicly hanged. Missak, 28, was a butcher who was well known for his beautiful voice. On page 108 of ‘In the Ruins’ Yessayan writes: ‘The story goes that, mounting the gallows, he sang one of his heart-rending songs, making even the soldiers standing around him shiver with emotion.’ (Photo: Mekhitarist Order, San Lassaro, Venice, Italy) Missak Sarkisian, one of the Armenians who was publicly hanged. Missak, 28, was a butcher who was well known for his beautiful voice. On page 108 of ‘In the Ruins’ Yessayan writes: ‘The story goes that, mounting the gallows, he sang one of his heart-rending songs, making even the soldiers standing around him shiver with emotion.’ (Photo: Mekhitarist Order, San Lassaro, Venice, Italy)Virtually everywhere Yessayan went she saw total destruction. »The wife of the English consul said of Mersin, “The whole horizon had turned red… The flames were shooting up in every quarter of town. … Human beings had turned into veritable devils. … I shall never forget those closed, ruthless faces, blackened by gunpowder, contorted with blood lust.” She told of a mother running across the rooftops to escape, holding her baby in her arms: “the shot went off and the child’s head dropped lifeless onto its mother’s shoulder. … Only after she reached us did she spot the hole in her child’s forehead. Veritable devils, veritable devils.” Yessayan herself, as she put it, “had resolved to maintain my sangfroid.” It would be difficult to do her work if she succumbed to her pain upon seeing the broken children she was attempting to help. Yet she could not shut off her empathy, and indeed that is what the children needed most:  Khatoun Vanoudian, four years old, who was wounded by the bullet that killed her grandmother. Her father and eighteen-month-old brother were also killed; only her mother survived. (Photo: Courtesy Judith Saryan) Khatoun Vanoudian, four years old, who was wounded by the bullet that killed her grandmother. Her father and eighteen-month-old brother were also killed; only her mother survived. (Photo: Courtesy Judith Saryan)Yessayan’s narrative is replete with stories of anguish, loss, maiming, the torching of entire cities, hundreds burned in a church, and thousands hacked to death, but this voiceless child became for me the sound that most deeply penetrated my mind and heart when I closed the covers of the book. Yessayan’s narrative focuses especially on the plight of families who had lost homes, fathers, husbands; children whose mothers gave their children up rather than see them starve to death; mothers who had lost all their children; old men and women, limbs missing, children missing, blind, without clothes, food, shelter. Yessayan also heard stories of how the towns responded or how they had not. Many villagers in the town of Abdioglu said their deepest regret was that they hadn’t resisted. As one man put it,” We thought they would spare us.” Upon hearing these words, a middle-aged man flew toward them, shouting, “Children of slaves! Grandchildren of slaves! Shame on you. ‘Life is sweet’! that’s true; but what makes you think that you deserve to live? Look at these poor women”—he pointed to the widows—“and tell me, honestly: What sweetness does life still hold for you? … We’ve been annihilated, we’ve been wiped out! … We were fooled like little children; we gave them what weapons we had, and they shot us down with the bullets we threw away. … This wasn’t the first time, or the second. …we played hear no evil, see no evil. Shame on us! …. Someone who doesn’t know how to die has no right to live. Children of slaves!”  An Armenian peasant, the only survivor from his family, holding the skull of his son. (Photo: Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute, Yerevan, Armenia) An Armenian peasant, the only survivor from his family, holding the skull of his son. (Photo: Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute, Yerevan, Armenia)Perhaps the most devastated community was that of Misis. One survivor who had hidden in a ditch reported: “There wasn’t an Armenian left in Misis, except for a few blacksmiths whom they converted to Islam and kept with them, since there aren’t any other blacksmiths here. … In this house, as many as sixty people were burned to death.” The vartabed from the Holy See of Cilicia, who had arrived the night before on business, was torn to pieces alive. Children were thrown into fiery pits and burned alive in front of their parents who were then thrown in after them. Yessayan and her group wandered through the defiled land finding “fragments of human bones, patches of burned, tattered clothing, a child’s shoe”: “From what fleeing child’s foot had it fallen? In what ruin had the foot wearing it turned to ashes? A little shoe…” The lone survivor said to them, “Traces of blood don’t disappear. So much blood flowed that there are places where even the ashes seem moist. You could clearly see how the stain, big and dark, spread outward.” Pages of mangled books swirled by “half-burned, half-stained with blood”: “I looked closely at one of the pages and, through a cloud of tears, read, ‘Lord have mercy on us and bless us; turn your face toward us and have mercy on us.’” After weeks of bearing witness to such monumental ruin and attempting to provide what respite they could, Yessayan and her team set on their way to Sis and then Dortyol, hoping for a relief from the atrocities committed in the rest of the province—and indeed they found it. »My grandmother spoke often of the fragrance of the orange trees in Dortyol, that sweet scent that wafted over the groves and across into the town. Yessayan and her companions could smell the “pungent, heady aroma” an hour away from Dortyol. Dortyol was a primarily Armenian town. Its inhabitants spoke Armenian, as well as Turkish, and they had a sense of Armenian identity and cohesiveness that much impressed Yessayan. Some Armenians from neighboring areas moved to Dortyol for protection. Among them was Mihran and his family who had pleaded with his parents and siblings to leave the town of Misis where his father was priest and go to Dortyol, an Armenian town where the family might be safer in the event of danger. My great-grandfather, Der Avedis, was the Der Hayr in Misis, and he did not want to abandon his flock, but Mihran tricked him by saying he had gotten permission from the church for Der Avedis to leave. Mihran’s prescience—and his duplicity—saved his family. Dortyol had received no assistance from anyone, yet 5,000 people survived in that town, some coming from outside to seek protection. As soon as the townspeople heard that Adana was under attack, they took an oath: “…everyone would die gun in hand. The next day, the enemy encircled and attacked us, thousands strong. United like a single man, all of Dortyol’s Armenians stood up to the savage mob. The enemy rained rifle fire down on us for fifteen days straight. The Armenians didn’t set foot outside the town. They reinforced their barricades from within, and fought bravely. Then their water ran out. All the men, young and old, were on the barricades. The women and children came and went under a hail of bullets to bring them provisions and ammunition. Two women even took up arms and joined in the fighting.”  Tavit Effendi Ourfalian, the president of the Armenian National Council of Adana and one of the first victims of the massacres (Photo: Mekhitarist Order, San Lazzaro, Venice, Italy) Tavit Effendi Ourfalian, the president of the Armenian National Council of Adana and one of the first victims of the massacres (Photo: Mekhitarist Order, San Lazzaro, Venice, Italy)“Every single stone had its history. Many were battered, pockmarked on the outside by the bullets fired from the Henri-Martinis. For quite some time, we sat on a pile of rocks that had tumbled to the ground and looked around us in almost total silence, our hearts overflowing…” After their long, horrifying journey through Cilicia, Yessayan returned to Adana. The tour through hell was over, but much remained to be done to rebuild. She ends her testimony with a story of Uncle Giros, an old man so grievously injured that half his face, including one eye, had been hacked off. He was not expected to live, but upon returning to Adana Yessayan found Uncle Giros digging in the dirt of his vineyard, breaking up clods of soil with his bare hands.» “It’s not for me, “he said. “Who knows whether I’ll be around to taste next year’s harvest? But I have my grandchildren. As soon as I got better, I went and fetched them from the orphanage. I need them and they need me.” Yessayan writes, “That evening, for the first time, we were perfectly happy. For, when we got back to the city, it seemed to us that Adana, an immense graveyard, was—slowly laboriously, but surely—rising from its ashes.” It would be a hopeful ending to the story of the Armenians of Cilicia—if we did not know what was soon to follow. All photos featured in this article can be found in the English translation of Zabel Yessayan’s In the Ruins published by AIWA press.» Special for the Armenian Weekly In the year of the Armenian Genocide Centennial, we saw hosts of books published on the genocide, attended many inspiring presentations, and began what we hope will be productive conversations to chart a course toward reparations. The Adana Massacres that began in April 1909, however, are sometimes overlooked, sandwiched as they were between the Hamidian Massacres of 1895-96 and the 1915 Armenian Genocide. These attacks in 1909 took the lives of more than 30,000 Armenian men, women, and children. Armenian Cilicia had been burned to the ground, many of its people trapped inside torched churches, leaving only charred bones to speak of their fate. Thousands of children were left orphaned or with broken, widowed mothers who could no longer care for them. The number of unprotected women, those who had lost husbands, fathers, and brothers, was over 10,000. Only two towns were left standing by September of 1909—Sis and Dortyol. A public hanging in Adana (Photo: AGBU Nubarian Library, Paris, France) The revolution of 1908 had reestablished the Ottoman Constitution, resulting for a short time in the lifting of censorship, the release of political prisoners, and a sense of hope that enhanced freedoms would [...] Special for the Armenian Weekly In the year of the Armenian Genocide Centennial, we saw hosts of books published on the genocide, attended many inspiring presentations, and began what we hope will be productive conversations to chart a course toward reparations. The Adana Massacres that began in April 1909, however, are sometimes overlooked, sandwiched as they were between the Hamidian Massacres of 1895-96 and the 1915 Armenian Genocide. These attacks in 1909 took the lives of more than 30,000 Armenian men, women, and children. Armenian Cilicia had been burned to the ground, many of its people trapped inside torched churches, leaving only charred bones to speak of their fate. Thousands of children were left orphaned or with broken, widowed mothers who could no longer care for them. The number of unprotected women, those who had lost husbands, fathers, and brothers, was over 10,000. Only two towns were left standing by September of 1909—Sis and Dortyol. A public hanging in Adana (Photo: AGBU Nubarian Library, Paris, France) The revolution of 1908 had reestablished the Ottoman Constitution, resulting for a short time in the lifting of censorship, the release of political prisoners, and a sense of hope that enhanced freedoms would [...] [img][/img] More... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|